Posted October 12, 2025 by Dr. Norris

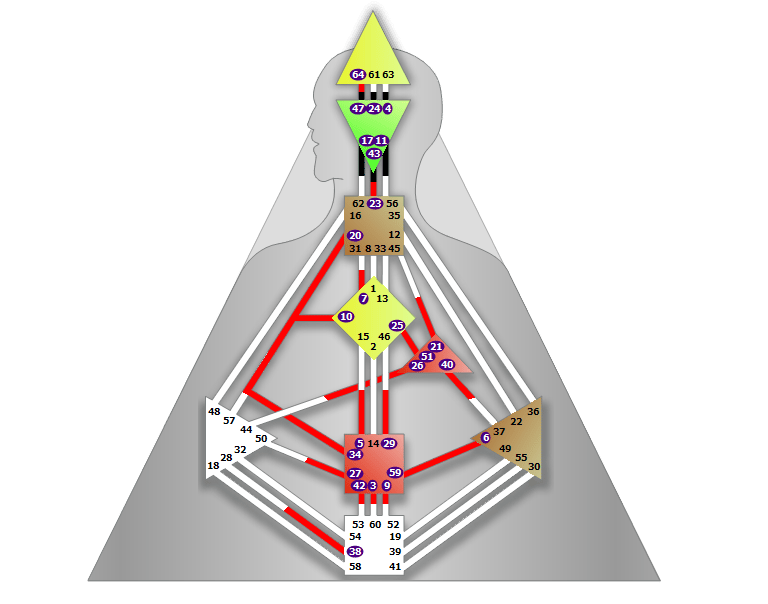

Neuropsychology & the Human Design Bodygraph

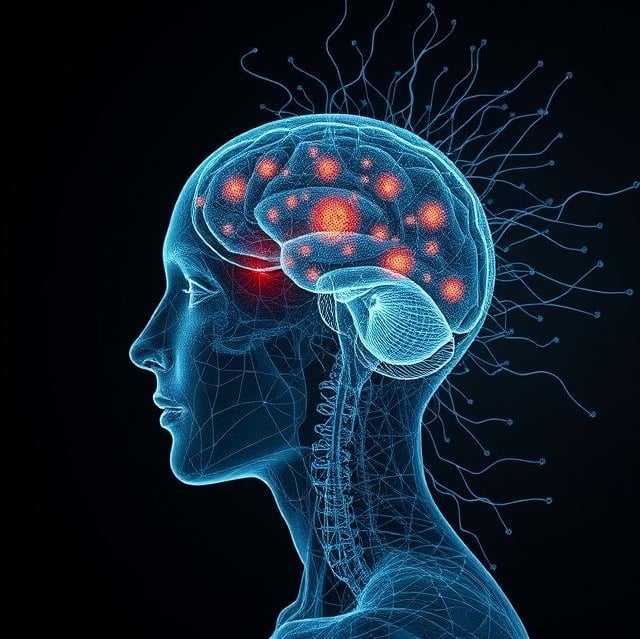

Neuropsychology explores the relationship between brain function and behavior and posits that all actions and interactions have a neuropsychological equivalent, whether adaptive or maladaptive. It is a field of inquiry at the forefront of brain-mind science. However, the brain-mind connection is also at the core of human design synthesis. Perhaps human design can offer individualized, integrative approaches to future neuroscience research. For instance, would there be any differences in brain function from deconditioned people raised from birth according to their design? More importantly, how can understanding the principles of neuropsychology deepen our understanding of human design mechanics, aid in the process of our own deconditioning, and enhance self-awareness? And what can the human design bodygraph itself show us in terms of neuropsychology?

Glycine: 47 - 64 - 40 - 6

Threonine: 11 - 26 - 5 - 9

Valine: 4 - 7 - 29 - 59

Asparagine: 43 - 34

Arginine: 17 - 25 - 21 - 51 - 10 - 38

Leucine: 24 - 20 - 23 - 42 - 3 - 27

"The Biochemistry of Thinking"

There are hidden relationships within the bodygraph between different centers, channels, and gates that are connected through the underlying biochemistries of our neuroanatomy, related to specific amino acids, neurotransmitters, hormonal glands, and physiological processes. For example, looking at the amino acid groupings involved in the Ajna center, we can see what other centers are involved in the process of conceptualization and begin to map out the "biochemistry of thinking" within the bodygraph. This approach not only brings up various topics from neuroscience (e.g, perception-to-action potentials, the gut-brain axis, the link between brain function and behavior) but may shed new light on specific channels that are revealed within this matrix (e.g., why the 34-20 has the word "thoughts" in its description, whether we are following mental convictions or the convictions of the body in the 34-10).

This visual representation of "thinking" might bring a deeper understanding to why we seem hardwired to think about certain things (e.g., intimacy and sex, what to say, what to do, how to win, our own awakening), why the mind thinks it can take control (i.e., all the gates of the ego center are connected to it), how mental arguments can explode into fighting from pent-up aggression (i.e., dormant gate 38 in undefined root), why the mind can never know what is healthy for the body (i.e., totally open spleen, the only center not involved in the Ajna's amino acid chemistry), and even the way in which the brain's central nervous system connects with and runs through the entire body (i.e., single definition).

Likewise, it helps explain how the process of thinking can create impulses or sensations in the rest of the body that directly affect our physiology on various levels and to varying degrees (e.g., sitting on the couch pondering what to do and the motor cortex in the brain starts firing before moving a muscle, thinking about spiders and the skin starts tingling on your leg, remembering a lover and feeling their embrace as if they were next to you). This layout of the chemistry of conceptualization points to the confusion that can arise between "top-down" versus "bottom-up" sensory-perceptual processing, which is a topic in neuroscience. Is it the sensory input from our body that is informing our conceptual and cognitive capacities, or is it the mind's assumptions and interpretations and expectations that are driving our body's experience?

As brain-mind science explains, in terms of brain states, there is little variation between perceptual, imaginary, and hallucinatory experiences. Listening to a song playing through speakers (external-to-internal perception) versus imagining a song playing in your head (internal imagination) versus thinking you hear music in the room when it's not actually there (internal-to-external hallucination)—to the brain, there is no difference. The line between what is real and what is imagined can be easily blurred. Put yourself in a noise-proof blackout chamber that's completely cut off from any sound and light, and you'll pretty quickly start seeing and hearing things. Our brains are hallucinating machines! Often, we suffer from things that we imagine more than anything else. Anticipation of something that may or may not happen can create just as much stress as an actual emergency situation that's physically in front of us. Thinking about something stressful can flood the body with stress hormones and trigger a fight or flight reaction, even when no threat is actually there.

It all points to specific neuropsychological principles, in that we can have very real physical experiences from things that we think are coming from other people or the external environment, when in fact what we are experiencing has nothing to do with the outside world and is only happening in our head. In the human design bodygraph, the Head center is pointed outside of the body. It can be totally disconnected from material reality, especially when perception gets distorted. There are even so-called "channels of madness" between the Head and Ajna centers that warn us of the kind of delusional thinking that is possible within the human experience: how we might rationalize our attempt to resolve the unknown by thinking that we know without verifying whether it's true or not for anyone else, how we can make sense of anything even if in reality it's nonsense to everyone else, how we can get lost questioning everything while searching for answers to find some hidden pattern that might not exist.

The brain is not designed for objective reality. It is a pattern detection machine. But the only data set it has is based on its past experience. When presented with something unknown or ambiguous, it takes what it knows from the past and superimposes that onto the future. The issue is that reality unfolds differently, things don't happen in the way we think they should, which creates anxiety and nervousness because life is not unfolding in a way we are comfortable with, and we can't control it. And so we begin to OVERthink and OVERstrategize and OVERcompensate and OVERreact, based on this energy of fear—fear of the unknown, fear of confronting something we know nothing about because it's not in our experiential data set. How could you say that?! What do you mean you don't agree with me?! Why can't you see that I'm right and you're wrong?! Why isn't the world a better place (based on my subjective perspective of how I think it should be)?! I'm so enraged!

But here's the thing. It's never about the details of the situation or the surface-level circumstance or even the goal that we think we want to attain. It's about the underlying neurobiochemistry between the nerve cells in the brain that transmit signals throughout the body, which we experience as a feeling state. It's a frequency. A fundamental teaching of human design is that the maia is frequency. A fundamental teaching of neuroscience is that the brain runs on frequency. Different brainwave patterns correspond with different states of consciousness. Certain frequencies are associated with specific feeling states that operate through the principles of resonance and determine what we are attuned to or not within our lived experience.

The brain creates a kind of algorithm that acts like a feedback loop to recreate specific feeling states that it's familiar with from its past data set getting constantly reinforced. And often there's an underlying feeling state that we are trying to avoid feeling again. In other words, the mental reasoning that we attribute to why we think we're upset is not actually what is upsetting us. It's not about "oh that person did this" or "this situation is causing that." It's not about the situation. It's about our relationship with the underlying neuroenergetic frequency that is being recreated in the nervous system, and the anticipation of pain that gets triggered when we are faced with uncertainty from the possibility of feeling something we don't want to experience. This boils down to one issue and one issue alone: our relationship with fear. I'm so upset because I'm being faced with something that I don't want to feel! I'm feeling anxious because there's something I'm afraid of facing! I'm holding on and not letting go because I fear for my survival in meeting the unknown!

So, the brain meets uncertainty, the mind predicts the worst, and instead of sitting with the unknown and just feeling whatever pain might come out of that, I'm going to instantaneously shift the narrative to blame something or someone outside of myself and push that something or someone away so that I can fight it as a defense mechanism to keep me from facing that energy within myself. The brain is hardwired with pathways to avoid pain and move toward pleasure, as a built-in survival reflex, but if we continually avoid certain kinds of internalized pain, certain kinds of stuck energy, certain kinds of past trauma, we will often recreate situations externally that keep bringing it up, as a mirror for what is unresolved within.

Simply put, we project our internal fears and feeling states onto the external world in an attempt to mold uncertainty to match familiarity, which sets us up for errors in judgment. The brain will manipulate the situation to fit its internal data set. And when faced with the unknown, it often stays with the pain it knows because the pain of actually confronting the unknown—either internally or externally—is perceived as more threatening, a greater pain, a more terrifying fear, a more oppressive anxiety. In essence, we get stuck in the conditioning that we know from the past, which colors our perception of the future, and keeps us from being able to see reality for how it truly is unfolding in the now.

It all points to how the brain handles itself when presented with the unknown and the mental story that comes out of that, which leads to adaptive or maladaptive behaviors. To put that another way, when faced with the unknown, where does your mind go? Do you start questioning things? Feel anxious? Nervous? Avoidant? Begin to fear holding on or letting go? Become insecure about whether someone else will hold onto or let go of you? Wonder if you're good enough? Want to prove yourself? Start oversharing? Get concerned whether you're going in the right direction or with the right others? Become restless like you have to hurry up and do something about it? Try to push for something more? Where does your mind start searching to fill in the blank?

In human design, we look to our openness, which is where we find our shadows, as well as our wisdom potential. So, on one hand, neuropsychology says that the brain has great difficulty dealing with uncertainty and meeting the unknown. And, on the other hand, human design says that all those places that are undefined or open in our bodygraph are precisely where we deal with uncertainty, where things are inconsistent, where things feel out of our control, where our mind develops defense mechanisms and survival strategies to avoid the pain of meeting the unknown in those areas of our life.

We each have an innate predisposition to process things in differentiated ways, based on the uniqueness of our design. What is normal to one person might be totally abnormal to another. How that person processes something might be completely opposite to how this person processes the exact same thing. Even two different people who were born at the exact same time with the exact same design will process things differently because they will meet different experiences in life, which changes their data set. As epigenetics tells us, both nature and nurture are at play. If you take two flower seeds that are genetically identical, and put them in different environments, they will produce different colored petals based on the conditions of their circumstances. Conditioning from the experiences we meet in life, especially involving pain or trauma, can change our biochemistry and rewire our brain.

From an evolutionary perspective, our brains are wired to reduce uncertainty at all costs because the unknown poses a threat to survival, and we become hypervigilant to potential threats at a neurobiological level. Research suggests that the experience of uncertainty comes with a heavy cognitive load that eats up our working memory resources, redirects our attentional energy at the expense of other cognitive tasks, degrades our ability to focus, and eventually leads to anxiety and overwhelm. Such psychic distress can get stuck in the brainstem and turn into a memory-based trauma response or fear-based trigger that distorts cognition and preconditions future interactions from our brain chemistry getting locked into a state of chronic hyperalertness.

It's painful to feel things that we're uncertain about, particularly things that may be true that make us uncomfortable to face, especially if they are about ourselves, where we might be wrong, where we might be blind, where we might be wounded, where we might be afraid, where we might have something stored inside that we don't want to experience again. It's much easier to deflect, project, blame shift, avoid, attack, and get lost in mental narratives that keep us isolated. But there are practical approaches to working with the energies of stuck fear and unresolved pain in ways that are constructive and transformational. Of course, it begins with self-awareness, which is how the mind ultimately heals itself.

In order to turn fear into awareness, we have to confront the fear, stop being afraid of it, and see its gifts. In the human design bodygraph, we know that fear is associated with the three awareness centers, which are all deeply related to our relationship with the world and others around us. Are you holding onto something—trauma, insecurities, unhealthy relationships, survival fears? Are you avoiding something—pain, guilt, shame, conflict, confrontation, truth? Are you trying to be certain of something to stay mentally in control—convincing yourself how you should or shouldn't think or behave, convincing others how they should or shouldn't think or behave, insisting you're right? Survival fear, emotional pain, and mental anxiety all have similar brain states. But in terms of differentiated awareness, each holds its very own cognitive potential. And that cognitive potential can be applied anywhere you look in the bodygraph.

So, how do you deal with meeting the unknown? What is your experiential data set? Where is your pain? What is your relationship with fear? What neuroenergetic frequency is being recreated in your nervous system? Is there an underlying feeling state you're trying to avoid? Is your mindset reactive or creative? Is your brain using you, or are you using it?

*

Summary of 15 Key Points

Meeting the Unknown

the brain always superimposes the past onto the future in an attempt to survive in the now when presented with the unknown

anxiety is a distorted relationship with certainty where the more we obsessively think we need to know the more anxious we become

fear of uncertainty drives us to overcompensate in an attempt to control the unknown rather than surrender to life and cultivate self-trust

unresolved energy stuck in the nervous system keeps us stuck in patterns of pain that we know such as avoiding our truth and continuing on people-pleasing instead of moving toward the more powerful pain of confronting the unknown by honoring our truth even if it's at the expense of others' approval

our perspective is never objective and is always based on subjective history that includes deep biochemical levels of innate intelligence as well as learned conditioning from rewired brain patterns that can be adaptive or maladaptive

short-term adrenaline can help move the body to survive but long-term stress can raise cortisol levels and lead to brain shrinkage

unresolved fear stuck in the brainstem recreates external situations in life based on internalized past trauma that colors what we think is happening and triggers us into overreactive defense mechanisms

fear-based trauma responses and survival-oriented self-protective trigger reactions can be associated with every center and seen through how we communicate and behave

different people we come in contact with open different brain processing pathways based on their designs and the principles of resonance

from a psychoneuroimmunology perspective transits and other people can trigger and lock in certain biological issues that affect mental and physical health especially in the not-self life

regular aura contact with others can change our physiology over time for good or bad

it's never about the surface-level situation but always about the underlying neuroenergetic dynamics at a biochemical level

shadow work using the human design bodygraph can help identify stuck energy that has been absorbed and amplified and distorted in the nervous system

deeper process work can involve not-self mind mapping going center by center to move away from thinking and speaking and acting from distorted frequencies when confronted with the unknown

the bodygraph is our brain-mind map and can be approached holistically from a neuropsychology perspective with therapeutic applications

Themes: Neuroplasticity, Cognitive Biases, Mindset, Trauma and Memory, Fear Transformation, Adaptability, Vulnerability

Special Topics: The Role of Mirror Neurons in the Process of Conditioning, Mu Rhythms and the Visual-Auditory-Motor Alpha Neural Network, Brainwave Entrainment, Dreams and Neurobiophysiology, Psychoneuroimmunology and the Onset of Disease from Transits or Other People, Tri-Brain Theory and the Splenic Streams, Trauma Responses and Gate 44, Left/Right Brain Hemispheres and the Crossovers in Collective Circuitry, Holonomic Brain Theory and the Holographic Body-Mind, Ajna Center Amino Acid Biochemistry

Acknowledgments: Ra Uru Hu, Martin Grassinger, Dr. Andrea Reikl-Wolf, Dr. Julia DiGangi